- Home

- Matt Pavelich

The Other Shoe Page 12

The Other Shoe Read online

Page 12

“You got your service weapon with you?”

“Always,” said the deputy. “Keep it under the driver’s seat.”

“Okay, but let’s try some other tricks first. If you really wanted to help, what I need you to do is untie that rope from the bumper, and take your end of it, and crawl out there on that bucket. Careful you don’t kick any levers or anything, and watch out for that hydraulic fluid. You get that stuff on your clothes, then it’s there for good, and I’ve even tried that powder they sell on TV. Doesn’t get it out. Wouldn’t want to piss your wife off.”

“Not married,” Lovell said. “I’d have to get a raise or a rich girl to do that.”

“Now, right there, right there where your foot is, no the other one, that’s exactly the set of knobs I don’t want you kicking. That’s right. Yeah, just shinny on out there. Nice of you to do this, by the way. Careful. Yeah, and look at this, I believe this belt’s gonna reach all the way around. Yeah, just the way we want it to. This could work out, believe it or not. Look at this, we’ve got plenty of belt. We are set.”

Lovell lost a handhold and fell sideways off the bucket and into the mud. He leaped up, slipped, and fell again.

“Take it easy, now,” Meyers advised him. “This clay’s slick when it’s wet. But don’t let that rope get away from you. I guess you’ll have to try getting up there again; shouldn’t be all that daredevil if you just remember to hang on.”

Lovell climbed out and onto the bucket.

Meyers directed him: “Tie up to that crosspiece behind you there. Now don’t tip outta there again, that’s not getting us anywhere.”

Meyers finished jury-rigging the belt and the singletree and the dangling rope, and he held the whole apparatus taut, standing on tiptoe in the muck, leaning on the cow’s heaving ribs. “Now, what you need to do is get down there and start the loader and pull up on that bucket just enough that I don’t have to hold this anymore. This’ll get old very fast.”

“I’ve never . . . I’ve never run one of those before.”

“It’s pretty easy. I’ll talk you through it.”

“I don’t think,” said Lovell, “that I want to take my first lesson with you standing almost right under it that way, Mr. Meyers. I’m usually up for anything, but not that. That could be bad.”

“Okay, you might have a point.” Meyers’s junkyard hoist was heavy, and his shoulder cramped with holding it up. “All right, I said you might get dirty. Hop on down here, then—no, get your shoes off, first, you don’t need to ruin those—come over here, and if you could just grab a hold of this outfit and pull it up tight, about like I got it, and hold it there until I can get the slack out with the bucket. Whole thing loses integrity, see, if you let any slack into the system.”

Meyers started the tractor again and slowly fed power to the bucket, and when his rigging was taut he supplemented the rope in his lifting system with a length of chain, and then from the driver’s seat he told Lovell, “You better back away from there now. I’m not too sure what this’ll do when I throw some torque to it, and you wouldn’t want to find yourself under a swinging cow.”

As Lovell retreated, Meyers moved the control forward gingerly and throttled up the tractor, and the pressure of the belt rising under her chest pumped an unearthly bellow from the cow, and she began to struggle with new energy, with terror, but still she could not suck free, and Meyers slid the lever slowly forward and the bucket pulled and strained and the tractor had tipped slightly to bear its weight on its front tires, and the whole assembly was in equipoise, the motor howling, before the cow finally, explosively sprung free. She’d scrambled halfway up the bank when the canvas belt dragged her hind legs out from under her, and she fell and rolled once in the mud, and she shot up and over the bank, and in twenty seconds she was grazing with almost no recollection of what had just happened to her. Meyers throttled back. He switched the tractor off.

“Did it look to you,” Lovell asked him, “like it broke its leg coming out? Or maybe broke its rib?”

“No, I don’t think so.”

“I could still shoot it for you, if you wanted.”

“She’s fine.”

“You just hate,” said Lovell, still standing in the ditch, “to see ’em suffer.”

“Maybe you do, but I kinda like it. The sonsabitches. They bring it on themselves. That old girl never has had the sense God gave a goose. What a project she’s been.”

Meyers told Lovell that they could rinse the mud off themselves in the stock tank, said the easiest thing would be to bathe in it, clothes and all. “This thing completely flushes itself, every two, three days,” he bragged, “it’s all gravity-flow. So it doesn’t matter if we muddy it up a little.” He lay back into the big round tank like a skin diver off a boat, and he spread his arms and legs as if to make a snow angel. The water billowed brown around him. “I’ve got perfect teeth,” he said, “and this is the stuff that did that for me—drinking it when I was a boy. All you really need is good spring water and organic prunes and plain beef. Maybe some bread and greens.”

“I’ve got the same thing going with Mountain Dew,” said Lovell. “That and Kraft Macaroni and Cheese. But anyway, I came to tell you I think I might have got a break in this case.”

“You did, huh?”

“I’m off-duty, but it just kind of came to me when I was sitting on my couch. I thought you better know what I found out because, you know, you’re probably the one guy who can do something about it. Thing was, I got called over to Red Plain yesterday to look into some vandalism that was done on Larry Manion’s lot. He had a car there that’d been left to be serviced, and somebody busted a window out of it, and he’s got to report it or he can’t make an insurance claim if he needs to. So I ask Larry, I ask him, ‘Who’s this belong to?’ and he tells me that’s the other odd thing, said that the kid who owned the car just wandered off, and he hadn’t seen him since. Wasn’t sure he was coming back for it. Or maybe it was even him—the guy—who broke the window, but why would he do that? Come back and break his own window?”

“So what’s your conclusion, John?”

“I think that might be our guy.”

“You ask Larry what he looked like?”

“I told him what our guy looked like, our dead guy, and Larry said he sounded pretty much like the kid who owned the car, who hasn’t come back yet, by the way. I checked with Larry again this morning.”

“Manion didn’t have any paperwork?”

“No. He said the kid left him a fifty-dollar bill for a sort of deposit and then he pulled some stuff out of his car, camping stuff maybe, and he took off. Afoot.”

“So you ran the plates to see who the car belonged to?”

“Yep,” Lovell was pleased that his thoroughness was appreciated. “It was a car out of Iowa.”

“And it belonged to a Calvin Teague. Calvin Winston Teague.”

“That’s right,” Lovell had already fallen a little behind; this always happened to him. He hated being the last to know.

“You didn’t call his people, did you?” Meyers heaved himself up and out of the tank. “If you’ve got a billfold,” he said, “you better remember to take that out of your pocket first. Days like this are exactly why I don’t carry one anymore. I bet I’ve lost twenty wallets in my life.”

“His people, you mean . . . ?”

“His parents, or wife, or whatever he might’ve had.”

“Oh, I . . . But how would I . . .?”

“Never mind,” said Meyers. “They’ve been notified.”

“Good.” Lovell let himself fall back into the tank as he’d seen Meyers do, but he did not know, as Meyers knew, that the springs were the fruit of a deep and frigid cavern. Lovell’s breath escaped him all at once, and, convinced he’d never retrieve it so long as he sat in this water, that his testicles might never again descend, he bolted out. Meyers loosed a rotten giggle, and the deputy shook himself like a dog.

“That’s a little b

risk,” said Meyers, “isn’t it?”

“Took me by surprise.” Lovell, once again the butt of a slight betrayal, did not appreciate having to be the good sport about it. “So now,” he said, “I guess you can go ahead and do some arrest warrants, huh? Now that we know who the guy is? I’m back on duty at six tomorrow, but I’d grab whoever you wanted me to grab as soon you could get the warrants done.”

“You think we better mobilize the National Guard?”

“Well, okay,” said Lovell, “I’m sure it’s not that urgent the way you see it. But when there’s an arrest, I want to be in on it. I really need that experience. I get drunk drivers. Them and wife beaters.”

“You don’t like wife beaters?”

“It’s kinda tame, usually, by the time I get there, or it’s got to where you don’t know who you’re supposed to restrain. You should hear the things people argue about, the reasons they give for hitting each other, stuff you can’t even believe.”

“I’d believe it,” said Meyers. “So, who was it you were you wanting to arrest?”

“No,” said Lovell. “It’s whoever you want me to. You say the word.”

“I just can’t think of anybody right now, but if I do, you’ll sure be the first to know. You should try not to get too excited on some of these things, all right? Your even keel, that’s the way to go. Over the long haul, you know.”

“They whacked that guy.”

“Whacked him? Where do you get this, uh, outlook? ‘Whacked’? The words you hear anymore.”

“What else could’ve happened? They killed him.”

“They did?”

“One of ’em did,” said Lovell. “I think the old man.”

“You mean the old, crippled guy? The guy who’s got everything he can do just to stand up? Him?”

“Well,” said Lovell, “somebody did. He’s still a pretty stout man, if you look at him. Been kind of tweaked, but he’s still strong enough, I’d say. And that girl’s no weakling, either.”

“All right, then,” said Meyers. “Which one? You pick.”

“Me? I’d say it was that Henry Brusett. He’s the man of the family, so . . . ”

“All right, and what’s the charge?”

“Murder?”

“Henry Brusett murdered him?”

“Well, he sure could have,” said Lovell. “Or she could have, too.”

“Yeah, and in either case ‘could have’ doesn’t cut it. I can just never impress that on you guys, can I? Do they teach any criminal law down there at that academy?” Meyers thought he might be more gracious to a kid who’d gone so far out of his way to lend a hand. “All right, here’s the theory, the principle, we’ve got to work with: innocent-until-proven-guilty. I’ll tell you right now, there’s many and many a case like this where I don’t have the goods to prove anybody guilty of any specific thing. So does that mean they’re innocent? No. Not in the way you see it, not the way I might see it, but in the eyes of the law . . . This is not a rare occurrence in the law, John, and if you just can’t take it, if the, you know, the weird result is more than you can stomach, then you might want to consider another line of work.”

“This is all I ever wanted to do.”

“You do it however you can do it. You come at it sideways, come at it backward. You do as much as you can, see what I’m saying?”

“No,” said Lovell.

“I am the guy who agreed to shovel out the barn,” said Meyers, “so that’s job security, but in the course of my day, my usual day, I never, ever make anybody happy.”

Lovell dipped his legs, one at a time, into the tank and agitated them, and scrubbed barehanded at his pants legs until they were clean enough to reenter the Corvette. “Somebody,” he said, after long conjecture, “did something up there.”

Meyers lost his patience. “Somebody’s always doing something wrong. But, look, we’ve got all these hardheads who always lived here, and now you also have the whole lunatic fringe of the United States moving in, all these people trying to hide out from the law or the dusky races or whatever, them and the military people retiring here, and down on the east end you’ve got your Indians, Native Americans that is, and it’s been my observation lately that just about everyone is pissed off just about all the time, and so you’ve got this bunch of assholes running around, armed to their grimy fucking teeth—and that is the one and only principle they can all agree on, their right to bear arms—bunch of yahoos just aching to plug away at each other, and they’re gonna play high minded and show everybody what a set of stones they’ve got with their gun. So the thing is, we get a good supply of cases. You’ll be in on plenty of cases, John, and on most of those you’ll have all the evidence you could ever want or need. I believe ballistics is their specialty down at the state crime lab.”

“What about this case, though?” Lovell’s face was, and would always be, a child’s face, fleshy, florid, and unlined, and he yearned for the lurid things so that he might solve the problem of evil, at least on the local level. He did not suspect of himself that he was a member of that sullen crowd Meyers had just described to him.

“What about it?”

“Well,” said Lovell, “it just seems like something should be done.”

“Why does everybody always want to do something? A real high percentage of the time about all you can really do is bear witness and wonder ‘What the hell?’ I tell ’em, I tell ’em all the time, over and over again: There’s nothing I or anyone else can do. I tell ’em, ‘I don’t know’ and ‘I don’t know’ and ‘I don’t know,’ till I get pretty damn sick of saying it, but that’s all there is left to say. I can only get so creative in the way that I handle these things. Do you see what I’m getting at?”

“No, I still don’t.” Lovell stood at his side, mistreated and conscientious, and he faced, as Meyers did, straight into the sun, and he held his shirt away from his chest to get some circulation behind it. Meyers could think of nothing more to say to him and began to wish that he’d leave.

Instead, Lovell asked, “Whatever became of your boy Bob? Jump-shot Bob.

“Robert?” asked Meyers. “Santa Barbara, been down there for years.”

“California? Why’s everybody have to go to California all the time? But I bet he makes a killing down there, doesn’t he? Probably rich, isn’t he?”

“Does pretty good. Throws pots.”

“Throws . . . ? Oh. Why?”

“Likes it.”

“Are they gardening ones, or for cooking, or what are they for?”

“It’s art. Does it by hand. They don’t do anything but look good, which is more than enough in California. He gets more from one of those pots than I ever got for a cow. Lives in a tent, got himself a sort of a sultan’s tent set up down there in the eucalyptus and madrona, and you can see the ocean from where he’s at. You can smell it. Oh, he’s got women, money, got a bulldog named Buster. No, Robert’s the first Meyers in quite a while that didn’t get himself tied to this sorry-ass country. So he did okay.”

“You don’t like it here?” Lovell marveled.

“I must, ’cause I never even thought of leaving. But it wasn’t for him.”

“You just never know, do you?”

“No,” said Meyers. “You don’t.”

When at last the deputy thought himself clean and dry enough to leave, Meyers set about restoring things to their usual places. He cleaned the long industrial belt and determined it was no worse for wear, and he guided it back onto the equipment it had once turned, onto the spools and rollers as if it might once again be called upon to spin the thirty-inch blade into a rusty blur. Meyers returned the singletree and the maul and the shovel to the barn. He parked the tractor and sat slumped in its seat. His exertions sometimes caught him unawares these days; having slept very little these last few nights he was almost dangerously tired, but he hadn’t finished picking up after himself.

Once he’d hoped to grow timothy here, or just any richer mix of grass, an

d to that end Meyers meant to run a spring-tooth harrow over it, but the lower meadow was too rocky even for that rough tool, and so he set out to clear the bigger stones, and Meyers would pick rock over the course of many years only to find each spring that a new crop of it had come out of the dirt for him, and in time he would build a wall with it to transect the whole property, with fancy stiles and a fancy gate. It served its purpose and did no harm.

Meyers parked his truck in the barn.

He cut a square out of an old canvas tarp and walked up to the place in the wall where, in 1978, he and Henry Brusett had commenced its construction. From here the thing had spread in either direction like a vine, and Meyers’s dedication to it had been a rare constant, as near to religion as he could come. He was thick through the shoulders and back for it, his fingers so thick he could barely type with them. Here lay his shame, obscured if not subdued; here lay Mike Callahan, the bottom piece of the whole structure. Though his every instinct balked at removing stone from this wall, Meyers began to lift it away. He worked his way down through the courses, and he had lifted tons of it away and was beginning to entertain the most macabre doubts when at last Callahan’s shinbone was revealed. Mike had been wearing jeans. Cotton. Nothing left of them. What had been cotton or flesh was gone, but Meyers collected on the tarpaulin most of the many small bones from Callahan’s feet, and, of course the larger bones, his legs and pelvis, and the rotten twist of leather that had been his belt, and a brass buckle, a flaring sun. Meyers took away ribs, and spine, and so many joints of his fingers as hadn’t somehow been washed away. These were very like gravel now. Teeth rattled out of Mike Callahan’s childish skull as Meyers picked it up. He gathered the rubber parts of Mike’s tennis shoes and a Ban-Lon shirt that hadn’t faded a shade since the day the boy had died in it.

Altogether, it made a small pile under the folded tarp. Darkness fell while Meyers rebuilt the wall, and then in darkness, with flights of pinwheels skidding across his eyes, he carried Callahan back down to his truck, and he drove down to the valley and into town. He went to the reservoir and stole someone’s rowboat to go out with the remains, enshrouded with a hydraulic jack for their aid and comfort in the underworld, and over what Meyers thought to be the deepest deep in the reservoir there was a burial at sea. No invocation, not even a splash.

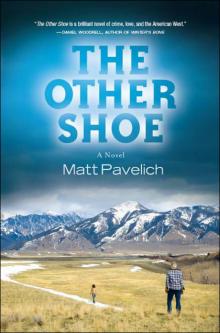

The Other Shoe

The Other Shoe