- Home

- Matt Pavelich

The Other Shoe Page 4

The Other Shoe Read online

Page 4

“Kid’s dead, and his blood’s all over Henry’s coveralls? That’ll raise some concerns. Neither one of you has a thing to say about it, so that does make people curious.”

“Cops?”

“Yeah, cops.”

“You,” she said.

“Not me,” said the county attorney. “I really don’t care to know. I can stand a little mystery now and then.”

“You must think I’m one of these real, real crappy people.”

“What I think,” he said, “is that you’ve got the right idea. And you should stick to it. Just stay quiet.”

“That’s your advice?”

“That’s my advice.” He expected it would be taken.

“So you’re on my side now? How did that happen?”

“I’m on your side, and I’m on Henry’s side, and I’d appreciate it if you’d tell him that for me. Make sure you tell him that, all right? I’m letting you know, and I’m letting Henry know that this shouldn’t turn out too bad for you. Especially if you can keep to yourselves about it.”

“So if we’re suspects—we’re suspects, huh?—but, if we’re suspects, aren’t you the other guy, the guy on the other side? Our enemy, kind of? Shouldn’t it be somebody else telling us what to do?”

“Usually, yeah. But—how to put it?—I’m gonna give you, both of you, all the benefit of the doubt. You see?”

“What are we suspected of? Exactly?”

“What do you think?”

“I don’t get what you’re telling me, then.”

“Keep a lid on it,” he said. “You’re both already inclined that way, so maybe this doesn’t have to be too bad. If you can keep to yourselves with it. Whatever it is. And, no matter what I do, it’ll be best for you guys to just keep quiet. In fact, it might be a good idea if you never mentioned this conversation we’re having right now. Except to Henry, of course.”

“You know Henry, too?”

“Man and boy I’ve known him. We were in that Belknap school together, that one-roomer Mrs. Callahan used to run. When I got my Rambler in the eighth grade I’d take him to school sometimes. School in town. That was before his folks lost their place down below us.”

“So, what’re you sayin’—you know he’s a good guy?”

“Right. He was when I knew him.”

“But a suspect?”

“Yeah, a suspect. I can’t do anything about that. It’s quite a long way from being a suspect, though, to being indicted, and it’s a long way from that to being convicted of anything. Lotta things can happen along the way. Henry’s always been one of the good ones, far as I know, and that’s my happy little understanding, and I don’t care to know anything different at this late date. I believe you’re all right, too, a good person. You and Henry are both good people—or good enough—so I’d like to leave well enough alone. If you see what I’m saying?”

“No. But I do know that if I did say anything, I wouldn’t know what to say. Let me off up at this turnout, would you?”

“Whatsit, five, six miles still to your place from here?”

“Maybe just three,” she said. “But I really do need to stretch my legs.”

The county attorney let her off on the highway, and Mrs. Brusett crossed it and set off up the road into Spurgin Gulch, her flip-flops sucking and slapping at her heels. Within a mile blisters had raised between her toes, so she kicked off her thongs and went on on grimy feet. Why couldn’t everyone just behave? Why couldn’t she? Why must every moment be lived in the bottom of her gut? She searched herself for forgiveness, just any forgiveness for anyone, but she’d still found none when she turned up a track that cut the kinnikinnick and wild strawberry and bear grass of a north-facing slope, and through a channel in a stand of dog’s hair pine, tall and dense, she climbed the shady road home.

▪ 2 ▪

GLUM AS A girl, she had stood outside her family’s happiness, betrayed by it, a tolerated guest at the many thousand ceremonies by which the Dents were forever appreciating themselves as plain but honest folk. It was this. More than anything else, it was this constant bragging on their honest ways that had made Karen so often despise them, because they lied slyly in their silences. Never a word passed between them, for instance, about the too obvious fact that Galahad Dent could scarcely stand to look at his daughter. His eyes might touch upon everything and everybody in a room, but when they came to Karen they went over, past, or through. He would look at her only so often and for only so long as was absolutely necessary, and then as if she were a stain.

How to speak of this? She never did, and so Karen was left to wonder; her earliest memory was of wondering, “What have I done?”

The Dents lived at the north end of Fisher Meadow in a trailer house at the end of two long ranks of Lombardy poplars. There were no neighbors. When Karen had lived there with her parents and her brothers, she had lived as much as possible out of doors, though she had no particular taste for solitude or, in those days, for so much unrelieved nature. She recalled marking time alone, breathing visibly off in some stubbled field or up a brushy slope. Her girlhood was bound on one side by life in the cold or among the pestering gnats, and on the other by her impatience for the daily fraudulence of what should have been her home.

For many years the hinge of Karen’s week had been Wednesday, because it happened that her mother got fed up at some point with the Good Shepherd and quit the church in favor of a Wednesday-night bowling league, and because her father would stand at the kitchen window watching Mother, as he called her, leave, and he watched her like a lost boy during the whole time it took her to disappear up the lane, and every Wednesday he fussed at the expense and trouble of her night out, and every time as she went out of view he conceded that Mother had earned and needed her nights of freedom from them. Then, usually, he would make potato soup for supper. This was soggy onion and potato, adrift in greasy milk. He served it merely warm.

“Go ahead and pepper the hell out of it,” Galahad Dent would tell his children, and the twins, wads of Wonder bread in their little fists, would fall to that soup like kittens to cream, for the boys loved everything, and their cheeks would ripen like pie cherries. Leave it to the boys to delight and prosper so in a meal that Karen could on no account bring herself to swallow, though Galahad would from time to time force her to try it again. “Who,” he’d ask her, as if she were someone he’d recently met, “who do you think you are? You can’t eat what’s made for you? Go ahead and be as stubborn as you want, but this is it. This is all the supper you’ll get.”

Karen could hold that soup in her mouth for a very long time. The stuff would pulse in her throat, and she’d gag and gag, but she had never given her father the satisfaction of seeing her puke. She held it until he was forced to relent and let her spit it into the kitchen sink, and then she was left with the vile aftertaste in her mouth. During these contests of will, a hatred vibrated her father’s voice so that even the twins were uneasy at hearing it, so Galahad would take them into the living room and wrestle with them, a pair of mewling, farting, relentless teddy bears, while Karen would clean up the supper dishes. He’d play with her brothers. He’d bathe them and put them to bed. He’d tell them—she could hear it from just down the hall—that he loved them. And then, sometimes, Galahad would put his head inside her door to say “good night.” Never more than that. In long, habitual hopefulness she would stand by her bed to await these visits, but then she’d be just enough startled when he came that she couldn’t find a way to answer, though she wished to somehow make a conversation of it. Once he had come all the way into her room, and he stood there for a while pretending fascination for the poster on her wall, a poster she had already outgrown but would never take down, a princess with a sparkling wand who was also, as it happened, a pig. Her father had stared at this until he began to tremble, and then he had surrendered a single, unprecedented tear, and when it reached his chin he told her, “Get in bed.”

“I’m . . . my jeans are k

ind of . . . well, they’re dirty.”

“Get in that bed,” he said. “And pull the covers up.”

After that he didn’t come to her door. Wednesday nights her father would put the boys down with a little story, and he’d go to the living room, and sigh, and turn on the television. Karen would sleep then, lulled by muffled laugh tracks and with her dreams buoyed up by the fact that tomorrow, while tomorrow might be many things, would not be Wednesday.

One day she was taken along with the other girls of her fifth-grade class to visit the office of the school health nurse. There the girls were given a short lecture on touching. Some of it was good, they were told, and some of it was bad. Emily Schact asked for clarification. Resigned to answer, responsible for some answer anyway, the health nurse inhaled deeply and her great bosom heaved. “It depends,” she said. There was a silent thirty seconds before Emily asked, “Depends on what?”

“Like I said before,” said the health nurse, “didn’t I already tell you this? It depends on who touches you. And where they touch you.” The health nurse illustrated her point with a drawing that was supposed to represent a girl’s body but looked more to Karen like one of the weatherman’s clouds, and it was for her purposes less illustrative. The health nurse pointed to it from halfway across the room, and one of the fifth-grade girls began to cry, several others to laugh. A second session was held the following week, and this time the health nurse had been joined by a county social worker to ask the girls individually, one by one and in promised confidence, particular questions about their experience of touching. Karen, thinking she was defending an indifferent father, told them that Galahad touched her all the time. Where? “Everywhere,” she said. Regular affection, she meant, affection in every room of the house. Touching. The health nurse and the social worker became grave and told Karen she could share with them anything she might need to say; they told her how important it was that she tell them everything. Their lips puckered in anticipation of hearing it. Karen thought that they must have seen through, and hated, her puny invention about being loved. “No,” she said. “This is that nice kind. Very nice. Probably the best, okay? Can we just leave it at that?”

Karen was not accustomed to very much of anyone’s attention, not yet accustomed to the necessity of having to cover her tracks, and she suffered the interviews that followed—talks with the health nurse and with Mrs. Hemphill, the social worker, and eventually, very secretively, with her mother—in deep confusion. Karen soon lost track of the facts such as they were, lost or misremembered those things she’d told them or failed to tell them previously, and by the time she was taken to the county attorney’s office she’d decided to stay quiet, to act as if she’d lost the power of speech altogether. Someone had mentioned their purpose. They wanted to find out if she was safe in her home, safe in the company of her father. Safe? Safety, as far as Karen knew, lay in looking both ways before crossing any busy road. The truth, they said. They just wanted the truth. The only reliable truth lay crouched in her heart, composed of nothing like words, and was nothing anyone, despite what they told her, would really want to hear.

She remembered that when she’d left the county attorney’s office that day, Mrs. Hemphill had huffed, “Well that really cuts it. We can’t do anything for you. Can we, Karen?” Karen had never imagined that anyone could, and had never asked for anyone’s help. She apologized, however, if only because that was what seemed to happen every time she opened her mouth.

Jean quit bowling after that, though she was carrying a 143 average in league play, and soon she had joined another church. She got busy at her sewing machine and made them all Sunday clothes so that they could attend services with her. Jean and Galahad and the twins were newly baptized, properly baptized at last, and the boys learned to speak in tongues, which they considered hilarious. Karen could never repent of her sins to the pastor’s complete satisfaction, and so she was weekly admitted to the Chapel of the Lamb but never gained admission to the church, not as a member. Both Pastor Hurlburt and Jean would frequently remind her of how they suffered, of how fearful they were for her as she stood in darkness, outside the church, stubbornly denying herself its warmth and light. But all this dreamy talk of dying or not-dying, and of big swings in the temperature and in people’s fortunes? A God so mean and grudging he’d require gratitude of men with holes in their filthy socks? She wanted no part of him. Having not found grace, Karen continued to haunt her family’s twilight, and she entered a trackless adolescence where even the thrumming of her powerful good health sometimes made her anxious.

Jean’s new religion required the doing of good works, so Pastor Hurlburt offered them a succession of rootless men who could benefit by exposure to the loving warmth of the Dents’ home and a decent Sunday supper. As Jean liked to cook, and as Galahad was willing to transform the floor plan of the trailer to accommodate a long table, and as his willingness extended even to going out and gathering up those selected strays who lacked transportation, most Sunday evenings in the Dent household now began to savor of Thanksgiving at the mission—good, aromatic food, bad hygiene, and, of course, our Heavenly Father to be beseeched and thanked for this and that. Not all their guests were bums or bums in the making, though, and it was at these Sunday suppers that Karen first encountered Henry Brusett.

Mr. Brusett was the only one of their guests to bring gifts for the household; it was safe to assume on Monday morning that the teapot left without explanation on the counter or the wildflowers tied to the screen door had been his offering. Among Sunday’s smelly pilgrims, few found the wherewithal even to say thanks, and even Mr. Brusett, who was so very appreciative, would never hazard to say more than that. He had come up in hippie times and must have been one, for he still wore his hair long, tied in back and center-parted, and it was streaked with gray so that his scalp suggested a skunk’s back. But he was not so glossy as a skunk, and not nearly so self-possessed. His right leg didn’t carry him so much as it had to be carried, and to be lifted and thrown forward in every troubling step, and Mr. Brusett was so unwilling to give offense that in company, to be safe, he ceased to acknowledge his own existence.

Karen saw—could she be the only one?—that Mr. Brusett was embarrassed by the needy whining the Dents shared in prayer. “Lord, please help Slim endure those frostbit fingers, and let Tony find a way back to the loving arms of his Lucinda, for we fear you, Lord Jesus, and from you all things can be given, and to you all thanks is due.” Mr. Brusett, looking away, looking at his feet. A man who spoke only as much as necessary to be polite, he was otherwise a blank slate, and each time he came, Karen imagined some new history for him. As his Sunday appearances became more important to her, Karen grew more and more certain that her parents would soon drive Mr. Brusett away with their loony devotions, with their Let-us-all-join-together-nows, their constant Let-us-now-bow-our-heads. Ordinarily, only very hungry men could stomach much of her folks’ blustery ministry, for the Dents’ preaching was the kind that incites sidelong looks. Galahad worked for the county road department, but he liked to think he was more than that. He owned his own home. He was fully insured. He had a nice wife and a nicer fishing boat, and he’d seen his salvation. It pleased him to lord it over the woebegone, and share his gooey rapture with them, and Pastor Hurlburt called Galahad Dent his great soldier in Christ. Her father, beaming in his certainty of life eternal, would say, “Christ died, boys, died on Calvary for my sins, and he’ll die for you, too, if you let him. He’d be glad to. Christ is Lord.”

And, worse, there was Karen’s mother, Jean. A mother who, out of sheer, sweet, unwavering incomprehension, had formed the habit of treating people like pets and conferring on them personalities having almost nothing to do with anything to be found in their actual characters. Jean would insist on everyone’s general decency, and that anyone who came through their door became honorary kin, and she called Mr. Brusett “Uncle Henry.” Every time Jean said something of that sort, Mr. Brusett’s head would bob slightly,

not in agreement, but another distinction, another little gesture that only Karen seemed to understand. He certainly never agreed to be taken in, but even so, and even though he kept no other company that anyone knew of, Mr. Brusett was their guest more Sundays than not for several years. That was the same set of years, as it happened, when Jean had taken to calling her daughter “Dad.”

And so Karen would try to meet Mr. Brusett at the door, and when everyone came to the table she’d try to sit across from him or to either side of him, somewhere within the scent of the astringent soap he used. His knuckles were large and egg-shaped and uneven; she saw that his hands, when not concealed between his legs or under the table, would often clutch at something not there. They were alike, she and Mr. Brusett; they’d made ghosts of themselves and learned how to go unseen. Only in his presence did she ever feel less than completely alone.

On a Sunday also memorable because she’d been mentioned in church for having graduated junior high, there came a new visitor to the dinner gathering, a fat man infatuated with his own name who talked rapidly and exclusively of Ned and Ned’s doings. Ned wore a yellow mesh cap streaked with some of the same greases it advertised. His hair and beard were cinder black and had been cropped to various lengths with clumsy shearing. In a half hour among them he had claimed to be the very best at some worthy thing which, unfortunately, he was not at liberty to describe or even name, and he claimed descent from Algonquins and presented the tips of his fingers as proof of it, and he told them he knew, more or less, what most of them were thinking. He said he didn’t mind. Mad in some barely governable way, Ned, it seemed, had known Mr. Brusett in years past, and he asked him about a woman named Juanita. Mr. Brusett said that Juanita was probably in Alberton with her new husband. What about Dave, then? Mr. Brusett, his voice an eggshell cracking, said that Dave was in jail, he thought. In the joint, actually. Deer Lodge. And Denny? Mr. Brusett shrugged with such finality that even the blithering Ned knew to let him alone. But Mr. Brusett was to spend no more Sundays at the Dents’. After that, Sundays were Ned’s, Ned who was not long in becoming, for Jean’s purposes, “Uncle Ned,” and the man, fascinated not only by his name, but by any name anyone might care to give him, would sometimes huff it like a toy train, “Uncle Ned. Uncle Ned. Uncle Ned. Uncle Ned.”

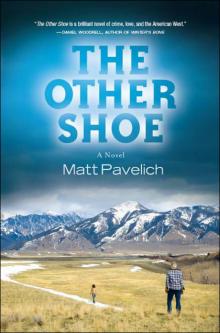

The Other Shoe

The Other Shoe